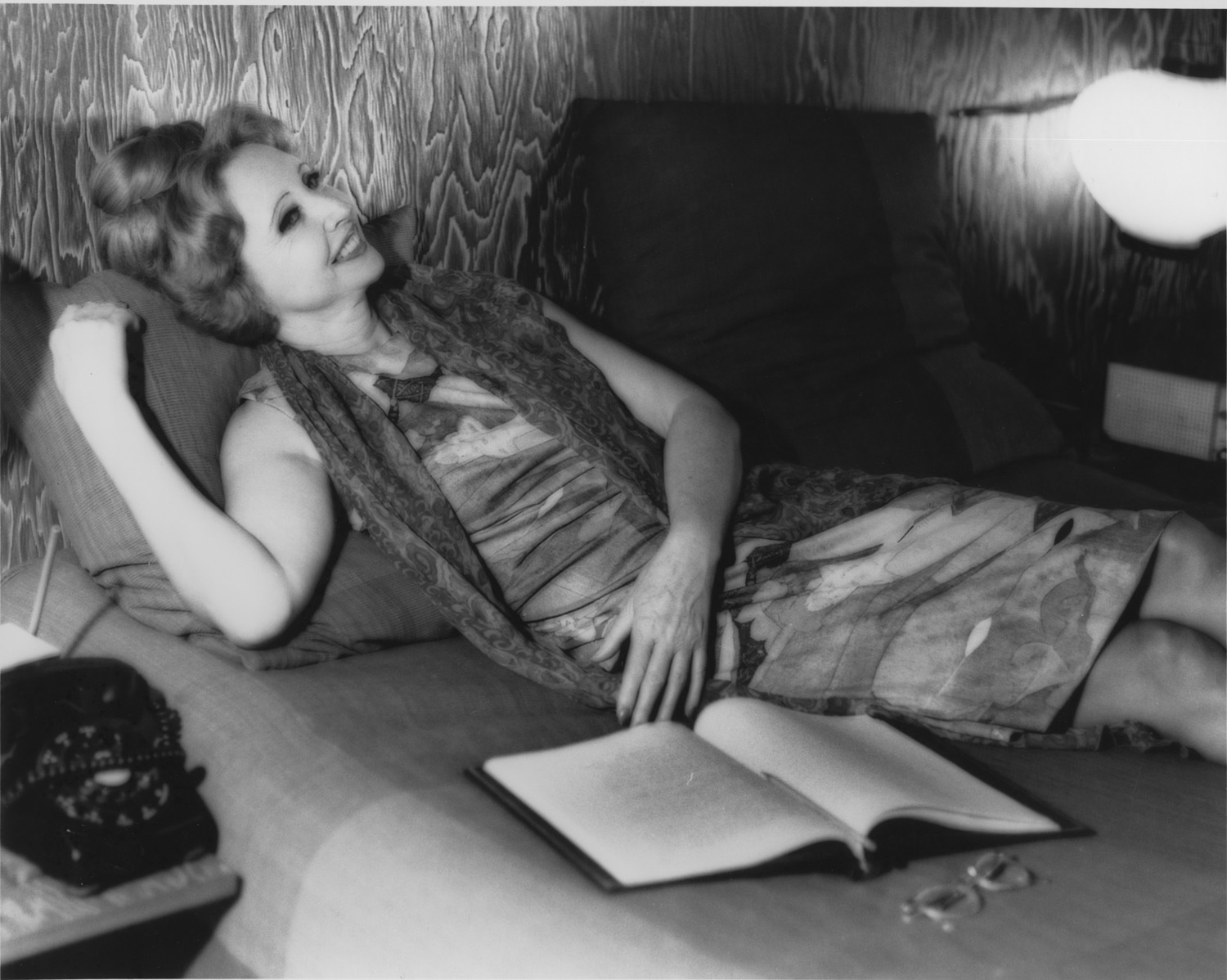

THE LEGACY OF ANAÏS NIN: A LITERARY PIONEER

The writer Anaïs Nin (1903-1977) is renowned for her diaries, novels, short stories, essays and erotic literature, and also for the relationships she cultivated with leading figures of the twentieth century. Although she published her first text in 1932 (“D.H. Lawrence: An Unprofessional Study”) her avant-garde philosophies—and her gender— meant she did not achieve wider recognition until 1966, with the publication of the first volume (of seven) of her diaries. Her honest depiction and evaluation of female desire contributed to the cultural shift away from old moralities and towards a sexual revolution. As second-wave feminism seeped into the mainstream, Nin connected with a new, young audience and frequently lectured at colleges and universities during her final decade.

After her death in 1977, her reputation declined in the wake of criticism of her personal life—Nin was a bigamist who conducted extra-marital affairs with both men (including her father) and women, and she fictionalized elements of her diaries for publication. She was cast as a narcissistic fraud and, by the late 1990s, seemed doomed to ignominy. However, twenty-first century readers have re-evaluated her life and work and a new, less morally judgemental generation now regard the self-awareness and insight of her writing as inspirational—and eminently quotable on social media.

Early Life: From France to New York City

Angela Anaïs Juana Antolina Rosa Edelmira Nin y Culmell was born on February 21, 1903 in Neuilly, France. Her Cuban father, Joaquín Nin, was a pianist and composer and her French-Danish mother, Rosa Culmell, was a classically trained opera singer. After her father abandoned his family, her mother moved Nin and her two younger brothers to New York City. Nin, then aged 11, began writing vivid impassioned diary entries, initially in the form of a letter begging Joaquín to return to them.Her father stayed away, but she kept writing her diary, at first in French then, after the age of 17, in English. It would become her lifelong habit.

The Paris Years: Artistic Exploration and Influential Friendships

Nin married her first husband, banker Hugh Parker Guiler in 1923. Guiler’s employers sent them to Paris, where his substantial income supported their artistic endeavors. Nin explored flamenco dancing and writing, while Guiler studied film-making. The newly-weds found themselves among writers, philosophers, and artists who were redefining creative boundaries and birthing the new movements of surrealism, Dadaism, and cubism. Nin’s social circle included writers Lawrence Durrell and Henry Miller, photographer-sculptor Brassaï, and actor Antonin Artaud. Her friendship with Miller, which began in 1931 as a literary connection, deepened into a passionate love affair. Nin was also seduced by Miller’s wife, June.

Anaïs Nin's Controversial Relationships and Psychoanalytic Journey

Nin’s first book, her 1932 study of D.H. Lawrence, praised his ability to depict female characters. Surrounded by male artists, Nin herself wanted to articulate a specifically female perspective, but felt unable to express herself truly. She turned to psychoanalysis as a tool to unlock her creativity, first with Dr. René Allendy, and then with Otto Rank. Both her therapists became her lovers. Nin followed Rank to New York in 1934 and spent a few months working directly with patients under his supervision, despite her lack of qualifications and the unethical nature of their relationship. She ultimately abandoned her plan to become a therapist and returned to Paris in the spring of 1935.

During therapy, Rank encouraged Nin to confront and heal her issues with her absent father. In the summer of 1933, she invited Joaquín to join her for a short holiday in Valescure, France. She wrote about it in her diary as ‘Father Story’, describing how they began a sexual relationship which lasted for three months before she abandoned him. This was eventually published in 1992 (as Incest: From a Journal of Love). The experience also generated Nin’s first book of fiction, edited with help from Rank, the prose poem House of Incest (1936). This was followed by a novel, The Winter of Artifice, published in Paris in 1939.

Literary Breakthroughs: From Self-Publishing to Critical Acclaim

The coming of World War Two meant Nin and Guiler relocated permanently to New York. Nin would spend the rest of her life in the USA, becoming a naturalized US citizen in 1952. In the 1940s, Nin struggled to find a market for her work. For quick cash, she wrote erotica for an anonymous patron for a dollar a page. She purchased her own printing press and learned how to operate it. Her self-published short-story collection Under a Glass Bell (1944) received praise from critic Edmund Wilson, but failed to establish her literary reputation.

In 1947, Nin met Rupert Pole in a Manhattan elevator as they were both on their way to a Peggy Guggenheim party. She was 44 and he was 28, but they felt an immediate connection. Pole thought Nin was divorced from Guiler, who was traveling overseas at the time, and they began a relationship. Pole lived on the West Coast, near Los Angeles, and Nin would fly out for weeks on end to be with him. They married in 1955 and Nin spent the next eleven years swinging on a “bicoastal trapeze” between the comfortable Guiler apartment in New York and scrubbing the floors of Pole’s forest ranger station in Sierra Madre. She eventually confessed the bigamy to Pole in 1966 and their marriage was annulled, but they continued their relationship until her death.

Nin continued to write and self-publish throughout the 1950s, gathering a small but devoted circle of readers. She had the ongoing support of Miller, Durrell, and Wilson, and the dreamlike poetry of her work also attracted praise from William Carlos Williams, Tennessee Williams, Oliver Evans, and Pierre Brodin. Her literary breakthrough came when independent publisher Alan Swallow printed the 800-page collection Cities of The Interior (comprising the continuous novels “Ladders to Fire,” “Children of the Albatross,” “Four Chambered Heart,” “Spy in the House of Love” and “Solar Barque”) in 1959, followed by her 1964 novel Collages, which was named one of the year's best books by Time magazine.

The Diaries of Anaïs Nin: A Cultural Milestone

Nin then focused on her diaries, submitting a heavily edited draft to publishers. Harcourt Brace agreed to publish the first volume, which covered her years in Paris from 1931 to 1934. The editing process was challenging, as many individuals, including Guiler, objected to being mentioned and requested removal. When the first volume of her Diary was published in 1966, it was celebrated as a significant literary achievement. Readers were captivated by the vivid descriptions of intellectual life in 1930s Paris, and Nin's psychologically insightful portraits of her friends and her journey toward self-discovery.

Later Life and Legacy

Following the publication of her Diary, Nin finally achieved the celebrity she had long desired. She was inundated with fan mail and requests for personal appearances. She also received critical accolades. She was awarded France's prestigious Prix Sévigné in 1971 and was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. In 1973, she was awarded an honorary doctorate from the Philadelphia College of Art. In 1974, she received an honorary Doctor Of Letters from Dartmouth and was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters.

Nin died of cervical cancer in Los Angeles in 1977. She named Pole as her literary executor and he arranged for the posthumous publication of uncensored versions of her diaries, along with her erotica and other volumes of work, before his death in 2006. Her persona and her work continue to inspire readers and writers around the world.